|

The National Portrait Gallery is in the news lately (see the case of Chuck Close) and I was reminded that Hedcuts are also included in the NPG. Since I had a hand in making it happen, here is my story. It was 2001, just a few months after the attacks of 9/11. The WSJ offices were located across the street from The World Trade Center, and our building was heavily damaged when the towers collapsed. In order to continue publishing a daily newspaper, our entire company and all of its operations had to immediately relocate to our parent company Dow Jones' corporate headquarters in South Brunswick, NJ. The newsroom was still in shock from the attacks. We were uprooted from our daily routines and to make things worse, we had to commute such a long way, it was hard to squeeze out even one drawing a day. There was also a lot of talk about company's restructuring at the time, which caused additional pressure on us. I was so demoralized, that was the only time I actually hated my job. Then one day, I was introduced to Anne Goodyear, curator of the National Portrait Gallery. She came to our office interested in including Hedcut portraits in the NPG collection. I was assigned a task of helping her, which worked wonders for lifting my spirit at the time. The task however, was monumental. Anne was interested in the history of hedcuts first and we spent long hours talking about everything hedcuts, from the evolution of the previous art styles, to all the artists who contributed their time and talents in creating the hedcut technique used today. When it came to compiling drawings, the task became even more complicated because a lot of our original artwork was destroyed during the 9/11 attacks, and archiving programs were still clumsy and not very reliable. In addition of going through hundreds of digital archives, Anne had to spend long hours in WSJ's storage building which housed decades of original artwork in dusty boxes. After a few long months of work, Online Hedcut Gallery was created and the WSJ donated all the needed artwork. 20 of my originals were selected, dating from 1989 to 2001, picturing public figures of the time. They include Steve Jobs, Warren Buffett, Oprah Winfrey, Steven Spielberg, Martha Stewart and a drawing of my future boss, Rupert Murdoch and his new bride. Click HERE to see the rest. Fast-forward to today. My technique of creating hedcuts, has changed significantly since the early 2000's. The paper's needs keep changing, our deadlines are shorter, the quality of newsprint paper is different, but most importantly, online display of hedcuts was ultimately the biggest influencer for continuous updating of my technique. When it comes to my process, the tools and art supplies I use, the biggest change happened when I was sent overseas to train the hedcut artist in our Brussels bureau. The Journal wanted the hedcuts used in the European edition of the paper to look more similar to the US edition's. In an exchange of artistry, the lady doing "European heds" introduced me to a completely new way of creating hedcuts and I use her system to this day. I plan on doing a post about that sometime soon.

1 Comment

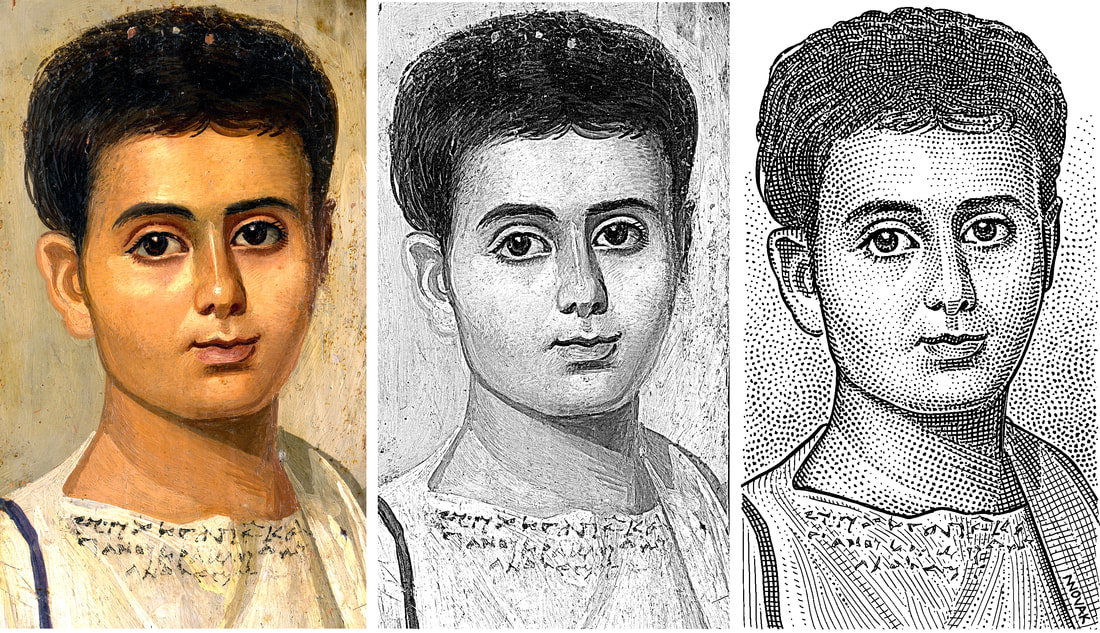

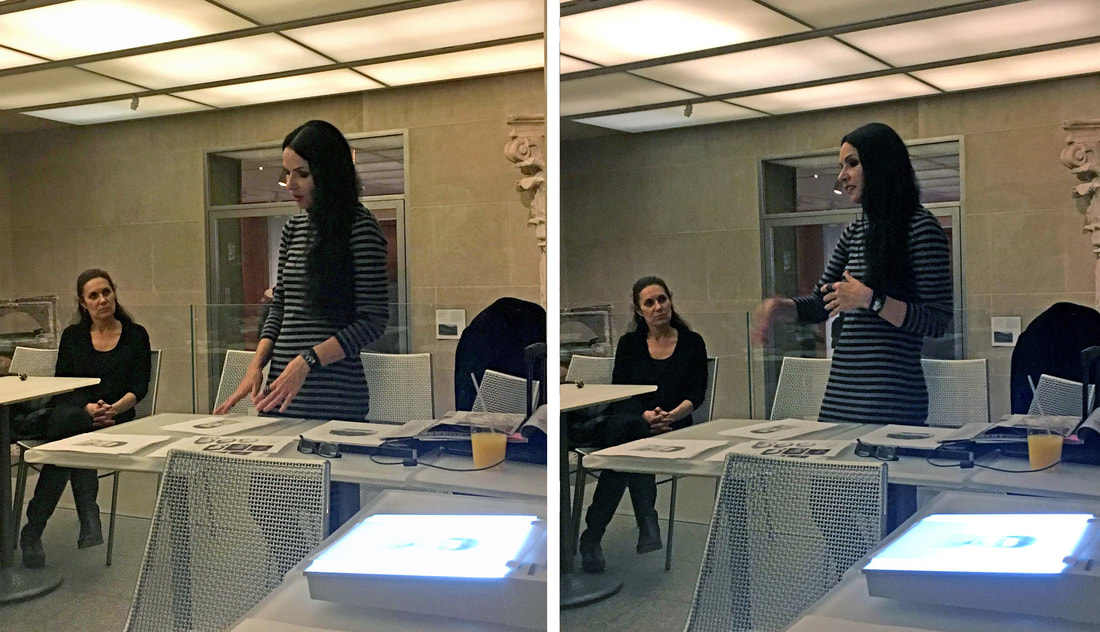

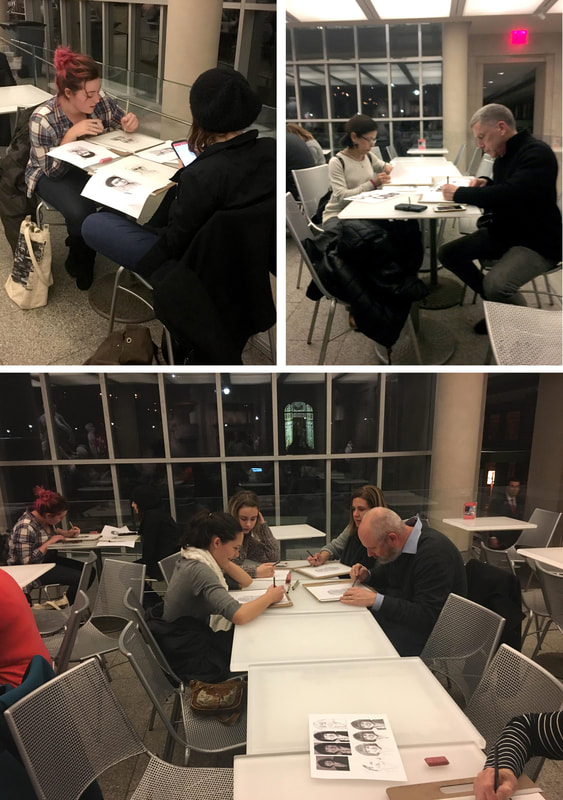

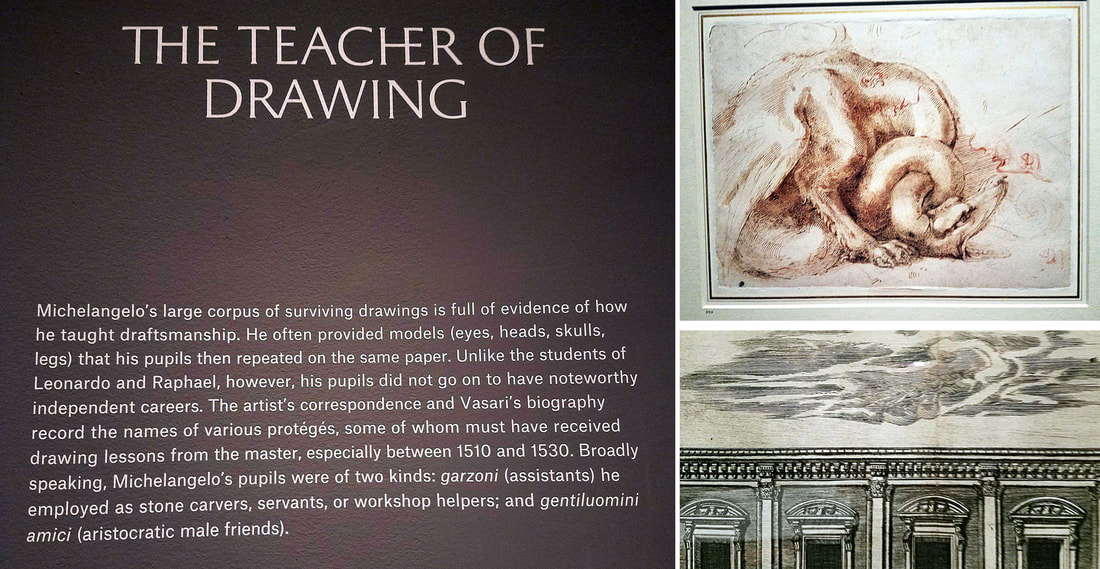

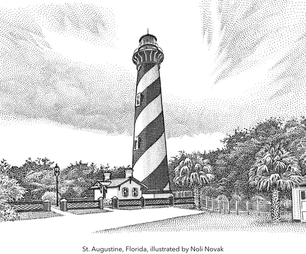

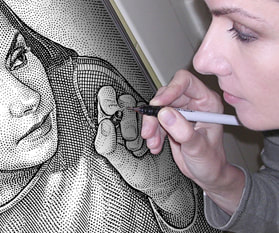

As per my invitation by The Metropolitan Museum in NYC, I participated in a public program organized on the occasion of the exhibition Michelangelo, Divine Draftsman and Designer. I held a workshop and showcase of my hedcut drafting technique for two groups of people interested in learning more about it. I was invited by Ann Meisinger, Assistant Educator for Public Programs & Creative Practice Education at The Met Museum. For the workshop, Ann preferred that we use reference images of some of the artworks from the museum's own collection. She picked a few, including a Fayum portrait of a young boy named Eutyches. I drew a stipple portrait of Eutyches to show the "students" what the actual hedcut would look like. From my experience of training the new artists for the WSJ, I knew that the drawing process might be a bit too technical for the attendees to master in an hour. On average, it takes about a month of daily practice for a person to start forming a cohesive style, but everybody in attendance was genuinely interested in giving it a shot. Most of the feedback from those who tried to draw, was that it is much harder than it looks. For instance, cross hatching needs to be smooth with the lines evenly spaced and dots have to be placed in patterns and even rows, both unique characteristics of the hedcut technique. At the WSJ, my colleagues and I have all developed our own, individual ways of doing hedcuts over many years of paper's constantly changing needs and deadlines, so at the workshop, I set up a few different ways of drawing. We had drawing panels, as well as light boxes and a variety of micron pens and vellum paper. In relation to the hedcuts, I checked out the Michelangelo exhibit. I focused mainly on his works on paper, more specifically his hatching technique and pen and ink line work which there were many examples of. In the end, I'd like to point out that my hedcut "workshop" was a very special event. I get asked about hedcuts quite a bit but I normally don't teach the technique outside of the WSJ. Therefore, I'd like to extend another huge "Thank you" to Ann Meisinger and The Met for the invite and the rare opportunity to do a little show-and-tell about real WSJ hedcuts. I was also happy to learn they are interested in doing a workshop with my paper collage technique in the future, which is very exciting. The Arts & Culture app, which matches selfies with classic artworks, was used on Wall Street Journal portraits. Outtakes from the article in Tech section of the WSJ, 1/17/18 Click HERE for more (subscription needed) Article in The Florida Times Union, By Matt Soergel, 1/12/18 Noli Novak, working out of her home studio in Riverside, is one of just a handful of artists who supply the Wall Street Journal with its iconic stipple “hedcut” illustrations — the lifelike, hand-drawn head-shots made up of hundreds of dots and dashes and lines. Over 30 years, she’s done thousands upon thousands of the portraits, of news-makers famous and obscure. Many people she’s done numerous times over the years, as they — and the times — change. She offers some insights: When drawing a near-photographic likeness of President Trump, you might think it’s his rather unusual hairstyle that would be the hardest thing to capture. No, says Novak. “He actually has crazy eyebrows. Nobody notices that.” She is one of two full-time stipple artists at the Journal, where she was hired while still in her 20s, a recent immigrant from what was then Yugoslavia. Though her newspaper work is uncredited, she’s well known in the world of stipple illustrations, sought out for freelance work from major corporations and exhibited in galleries. And on Friday she’ll be at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where she’ll showcase the technique and invite those in the audience to try it out themselves. She’s not crazy about the cold anymore — never was — but it will be good, she says, to be back in New York. Until Sept. 11, 2001, she worked out of the newspaper’s headquarters next door to the World Trade Center. On that morning, she was at her apartment in New Jersey, getting ready for work, when a co-worker called to say something had happened at the World Trade Center. Novak turned on the TV, then looked across the Hudson River and saw the second plane hit the south tower. Then she watched as the buildings came down. It was nightmarish, unbelievable, she says. The Journal’s offices were badly damaged by the collapse, and Novak lost years of work she’d stored there. After that, illustrators began working from home. Within a few years, she moved to Jacksonville, where her husband, George Cornwell, had grown up. They’d met in New York, playing music, and formed a band that ultimately became known as NovakSeen. They played at well-known New York clubs, were signed by a German record company, toured Europe. She sang, and he played the guitar. She smiled: “We were loud guitars, drums, punk rock, metal, kind of a garage band. The ’90s were our era, up in New York.” Even so, they’ve played occasionally in Jacksonville, and she has long black hair and dark-rimmed eyes that suggest both her artistic and musical lives. After New York, Jacksonville seemed a good spot: warmer weather, no commutes, cheaper rent, more room for George’s fine-art printmaking studio. They settled downtown at first, figuring that was the spot, but soon grew disenchanted. “There was no central scene where I could find myself hanging out with people I had something in common with,” Novak says. Moving to Riverside, a short distance away, solved that. Cornwell now has a studio at CoRK, the artists’ studios in a warehouse on the edge of Riverside. Novak says she came up with its name — the Corner of Roselle and King — and enjoys spending time there. She needs the camaraderie of other artists and does some collaborative work there. Her Wall Street Journal work, though, along with a steady flow of freelance work, comes to life at her home, a brick building she jokingly calls the ugliest house in Riverside. She has a second-floor work-space, complete with a balcony, overlooking the street. From there, she can see people walking or biking or driving, can say hello to friends. It’s no New York, to be sure, but it suits her need for an urban neighborhood. “I’m definitely not a suburban type of girl,” she says. She doesn’t drive — never has — but from home she can walk or bike to Publix, stores, restaurants, CoRK and its environs. She grew up in communist Yugoslavia, in what’s now Croatia. Her hometown, Zadar, is an ancient city that was largely destroyed by Allied bombing in World War II. Her father was a photographer, and she still has hundreds of negatives he shot of the damaged city; she’s trying to figure out how to preserve them and have them exhibited back in Croatia. As a child, she studied music and art; when she was about 10, one of her pieces of art — a paper collage of men and women dressed in national costumes — was chosen to be a birthday president for Yugoslavia’s President Tito. She keeps ties to her homeland: Every year, she and her husband return to a small stone cottage they built in the traditional style on an island in the Adriatic. Novak continues her Journal work even from there. Each assignment begins with a photograph, sent by editors. “I’m given this one photo. That’s all I know about this person. Sometimes the photo is very bad, yet I’m supposed to capture the person in this style,” she says. From that photo, she traces the face’s major details, then, using three different Rapidograph pens, she begins creating the portrait in a meticulous process using dots, dashes and cross-hatching to create hair, clothing, shadows and light. Each hedcut takes between two to five hours, usually, to finish. “This is the look of the Wall Street Journal,” she says. “It’s totally iconic for the Journal.” As befitting the Journal’s focus on Wall Street, the stipple art is meant to resemble old-fashioned engraving found on currency bills. It’s designed to be uniform, but she can always spot the work of her colleagues: each person has his or her style. It’s a craft that passed down from person to person, Novak says. She trained some of the freelancers that the paper uses, and says it takes several months to learn the process. Many of her subjects are famous: Queen Elizabeth or President Obama, Steve Jobs or baseball legend Cal Ripken Jr., her subject on a recent day. She drew Hillary Clinton numerous times over the years too, as a new portrait was needed with every hairstyle change. Martha Stewart, by the way, was never happy with any of her hedcuts. Often though, Novak doesn’t even know her subject’s full name or their significance. All she has is that photo to work with. “Sometimes I have to read their minds, looking at the picture. Maybe I have to cut down on the double chin, but I need to to make them look like themselves,” she says. “I try to read their minds: What kind of person are they trying to show?” Matt Soergel: (904) 359-4082 A conversation about my work and career as an illustrator and musician. Many thanks to Patrick Fisher from The Cultural Council of Greater Jacksonville. Click HERE.

I'm honored to have been personally invited by the Metropolitan Museum in New York City to participate in a public program on January 19th that is being held on the occasion of the exhibition Michelangelo, Divine Draftsman and Designer. Museum visitors will have an opportunity to engage with a variety of different types and styles of drawing. I will be showcasing my pen and ink stipple technique, better know as "WSJ hedcuts". I will share the process and give the audience a chance to experiment and try out drawing in the museum, This will take place at 6 and 7 pm Floor 1, Gallery 162, Leon Levy and Shelby White Court and Galleries. Click here for more info: Met Fridays

|

POSTS:

-Mother's Little Angels Art Exhibition -Folio Weekly article -Meet the WSJ Hedcut Illustrators -History of WSJ Hedcuts -It's the Puppy Bowl! -Hedcuts at The Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery -Showcase at The Met -Arts App & hedcuts -FTU Interview -CCoGJ Interview -Hedcuts at The Met -Hello New Blog Categories

All

ARCHIVES

February 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed